What Can Jane McCrea Tell Us about the American Revolution Today?

By Blake Grindon, Princeton University

December 1, 2021

In the middle of the nineteenth-century, prominent journalist Benson Lossing reflected on Jane McCrea: “The sad story of the unfortunate girl is so interwoven in our history that it has become a component part.” Just over a hundred and fifty years later, Lossing’s claim may seem a little far-fetched. Jane McCrea was woman of Scots-Irish descent who was killed during the American Revolutionary War, probably by British-allied Native warriors, near Fort Edward, New York. I know McCrea’s story because I grew up only two hours from Fort Edward, and passed by Union Cemetery, where she is buried, on family drives as a child. For people who don’t live in or close-by upstate New York, however, McCrea is pretty much unknown today. So, was Benson Lossing wrong? What does it mean that Jane McCrea was a “component part” of United States history, and then almost completely vanished?

In 1860, it looked like Lossing was right. A brief survey from the time of her death in 1777 through the early twentieth century shows her name popping up again and again. Not only in Lossing’s hugely popular Pictorial Field-Book of the American Revolution, but in other histories of the Revolution, as well as novels, newspaper items, travelogues, and local histories. An image of McCrea’s death was even included in bronzes decorating the Saratoga Battlefield monument, erected to commemorate the first major American victory over the British Army, in October of 1777. Her apparencies weren’t confined to the Hudson Valley, or even to the United States—one of the early accounts of McCrea’s death was a novella published in Paris in the 1780s.

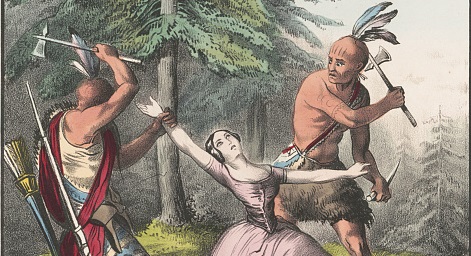

In all its popular manifestations, the McCrea tale was good stuff, filled with romance, violence, and tragedy, and featuring an attractive victim and ruthless villains. Though details varied among the tellings, the typical narrative went something like this . . . At the start of the American Revolutionary War, Jane McCrea was a beautiful young woman engaged to a Loyalist officer. In 1777, the British Army under General John Burgoyne was advancing south from Canada. McCrea planned to wait and meet her Loyalist fiancé so they could marry, but Native warriors, paid by Burgoyne for scalps, killed her and brought her scalp back to the army where her horrified fiancé learned of her death.

The popular appeal of such a riveting and romantic story is obvious. But it was also a politically useful tool, both during the war and after. It cast the British and Native American forces who fought against the infant American republic as heartless perpetrators of terrible violence, even against innocent Loyalists like McCrea. Thus, the yarn had staying power, remaining popular decades and decades after the actual event. It found renewed life in the nineteenth century, as the United States engaged in Native extermination and continental conquest. As the twentieth century dawned, and white Americans began to shy away from frontier violence, McCrea’s death became less useful, and, in its disturbing details, even a little inconvenient.

Behind McCrea’s often-repeated story, though, was the death of a real woman in a real war. Nineteenth and early twentieth century historians, like Benson Lossing, James Phinney Baxter, and William Stone, debated the myths around her death and tried to untangle fact from fiction. But ever since, McCrea’s life has been treated as just another story, an interesting example of rhetoric in the American Revolutionary War. I argue it is high-time to return to the story’s roots and dig deep in the actual event, taking a fresh look at a stale story. What we find may surprise us!

Jane McCrea, and her death, are remarkably well-documented for an otherwise unremarkable woman living in eighteenth-century North America. We know details of her family, the church her father founded, what her older sister, Mary, and Mary’s husband John Hanna, looked like, that her older brother John was a lawyer, and that that her younger brother, Steven, was a doctor in the Continental Army. We know the people who Jane was with in the hours before she died, Sarah McNeil, a family friend, and Eve, a woman of African descent who was enslaved by Sarah McNeil in her household. We don’t know if Jane was engaged to a Loyalist officer, but she was friends with a nearby family, the Joneses, who were Loyalists. We may even know who killed her, thanks to the Mohawk clergyman Eleazar Williams.

In the mid-nineteenth century Williams wrote a biography of his father, Life of Te-Ho-Ra-Gwa-Ne-Gen, Alias Thomas Williams. He mentioned that there were rumors that the men who had killed McCrea were from Akwesasne, near to Williams’ home village of Kahnawake on the St. Lawrence River. While in Wisconsin, Williams had met “a Winnebago [Ho-Chunk] chief [who] related to him more than once of his having had a hand” in Jane McCrea’s death. It’s impossible to know if Williams’ story of the meeting—or that of the unnamed Ho-Chunk man of McCrea’s death—was true. However, many of the details Williams included in this account of his father’s participation the American Revolutionary War are corroborated by other first-hand recollections. There were warriors from both Kahnawake and Akwesasne on Burgoyne’s campaign, and there were also men from much farther west, including Anishinaabe warriors from the Great Lakes region, and perhaps from the Ho-Chunk Nation as well.

Why did these warriors join in the war? One of the details Williams mentioned that can be verified was the presence in the Burgoyne campaign of several men who had formerly been officers in French colonial troops in Canada. They had been key to Native alliances with France, and were crucial to the decision of these communities to send their warriors along with the British army. Though Britain, not France, controlled the colony of Canada after 1763, these former officers continued to use their valuable linguistic and military skills in negotiating cross-cultural alliances. In 1777, they continued a long-established pattern of negotiating relations with Native nations and of fighting alongside Native war parties.

When Wabanaki, Haudenosaunee, and Anishinaabe warriors joined with former French colonial officers to fight a war in the Hudson Valley, they were acting in their own interests and following old patterns. By the 1770s, Native nations in the Northeast were increasingly concerned about threats to their lands and livelihoods, as a booming British colonial population pushed into their territories. Between 1763 and the start of the American Revolution, many British colonists settled on lands that they had previously thought were too likely to be attacked by Native raiding parties to support colonial occupation. It was, according to Tench Tilghman, an officer in the Continental Army, “a country intirely settled” since 1763. Among those colonists were the McCrea brothers, John, William, James and Samuel, who came from their home in New Jersey. In 1773, they were joined by their sister, Jane.

When the British Army and their Native allies reached Fort Edward in 1777, relations between them had soured. Native warriors resented the fact that the haughty Burgoyne saw them as subordinates, rather than as allies fighting in a common cause. They were also angry that he expected them to act as the advanced guard of the army, forcing them to take the brunt of guerilla fighting while his soldiers waited for the opportunity of a pitched battle. After a disastrous defeat at Bennington, where Native warriors from Kahnawake bore some of the heaviest losses, the surviving warriors demanded redress. Their concerns were dismissed by Burgoyne, and they left the campaign. The warriors who remained behind were increasingly interested only in fighting their own war against the region’s inhabitants, rather than the one the British command believed they were there to fight.

In August of 1777, Native scouting parties fought the retreating Continental Army and local inhabitants in brutal small-scale warfare. Among these was a skirmish with the militia at Fort Edward, were Native forces killed a Lieutenant, Tobias Van Veghten, and attacked Sarah McNeil’s house, with McCrea inside. Van Veghten and McCrea’s bodies were found the next day. Examining the circumstances of McCrea’s death reveals a story different from many of the details of popular histories. It’s not one of a woman trapped between two armies, waiting to marry a man in one of them. It’s one where women’s stories, the stories of the enslaved, of Native people from the Great Lakes and the Northeast, and of French Canadians, are inseparable from creation of the United States. That is a version of the American Revolutionary War that can seem oddly familiar to the cacophonous experience of living in America today. What if Lossing was right, after all? What if Jane McCrea’s death is a “component part” of American history?

Blake Grindon is a Ph.D. candidate at Princeton University and the inaugural recipient of the first Omohundro Institute-Fort Ticonderoga short-term fellowship. She used the fellowship to continue research on her project “The Death of Jane McCrea and the Contest for Warfare in the Northeast: Natives, Colonists, and Europeans in the American Revolutionary War.”