From Day to Piseco: The Life of Adirondack Guide Ira Shires

By Dave Waite

What makes a good Adirondack Guide? A lifetime of living in the wilderness, you may suggest. Or, perhaps, orchestrating fruitful fishing and hunting experiences. While these skills are certainly relevant, more often than not being a successful Adirondack Guide has been about providing friendship and companionship on the long and arduous mountain adventures.

Once such gifted guide was Ira Shires. A laborer and farmer, Shires became a celebrated escort and friend to many sportsmen at the hunting and fishing paradise of Piseco Lake.

Born in 1818 to Henry and Martha Shires in Day (a town in the northwest corner of Saratoga County), Ira was the fourth of eight children. Ira’s father was born in Connecticut around 1787, and by 1809 had come to Saratoga County, married, and engaged in agriculture. For the next sixty years, Henry and Martha devoted their lives to farming and family.

It was in Day that Ira met his future wife Sarah, whom he married in the early 1840s. Sometime before 1850, Ira took his family to Athol, in Warren County, where he spent the next ten years working as a laborer. During this time, Ira and Sarah produced four children, with Clarence born in 1846, and their youngest, Sally, born two years later. Living with them was Ira’s younger brother Hiram, who later in life became a Methodist preacher and operated a shoe repair business in Batchellerville, Saratoga County.

By 1860, the Shires had once again relocated, this time to Wells, in Hamilton County. There, Ira, following in his father’s footsteps, took up farming. But on the side, he began working as an Adirondack guide.

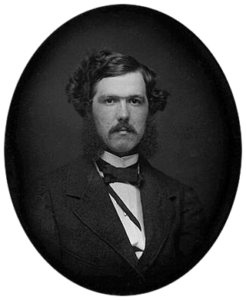

One of Ira’s early experiences was leading a group that included future president, Chester A. Arthur, who had lived in Cohoes and studied law in Ballston Spa. On that same trip were Arthur’s brother-in-law, James H. Maston, postmaster of Cohoes, and Edwin Purdy, of Amsterdam. When reminiscing about the time, Ira remembered Arthur as a “fine-looking young man, a fine man, and good company, too. I tell you.”

Chester A. Arthur in 1859

Ten years later, the Shires found themselves in Mayfield, Fulton County, where Ira continued laboring as a farmer. Still at home were 24-year-old Clarence, who was likely disabled, and 22-year-old Sally, yet to be married-off. Within the next decade, Ira finally abandoned farming for work as a full-time guide. The 1880 Census for Arietta, Hamilton County, lists 62-year old Ira’s occupation as “fishing and teaming.” With him were Sarah and Clarence, and living next door was Sally, after her marriage to Eugene Abrams.

Surprisingly, it was in Ira’s later years that he came to enjoy notoriety as a skilled Adirondack guide. The first news of his mountaineering career, however, was how he nearly came to an untimely end in the summer of 1882.

While guiding a group of hunters and their dogs along the shore of Piseco Lake, the men encountered the tracks of a large bear. Ira warned the party to stay close together and only fire when they could make the shot count, as bears were often aggressive in the early days of summer. One of the sportsmen, a Bostonian named William Milliken, took off ahead of the others and soon encountered two adult bears and three cubs. Startled by their sudden appearance, his aim was thrown off and he missed his target. A 400-pound male bear quickly attacked, killing four dogs. He then set upon the hunter. By the time Ira appeared, Milliken was dead, with the bear and its mate ready to protect their lives again. Before Ira could suffer a hunter’s fate, however, the rest of the party arrived and destroyed the bears. Though gravely injured in the encounter, Ira recovered, and by 1885 was again guiding sportsmen.

But Ira was far more than a seasoned hunter and hardened hiker, he was a truly talented fisherman. And by the mid-1880s enjoyed some local renown.

The July 8, 1885 edition of the Amsterdam Democrat, for instance, gives the following account of Ira’s prowess with a fly rod:

“To see Mr. Shires handle the fly was a ‘liberal education.’ At all times, even when the biggest trout was securely fastened to it, he was ‘as cool as a cucumber.’ Having stationed his ‘assistant’ at a convenient spot, the veteran guide would let the gamey fish whisk his line through the water, meanwhile, laughing and joking; ‘let him play awhile if he wants to; stand right where you are and I’ll bring him up pretty soon’ – and then we’d land the beauty and experience one of the ‘proudest moments of our life.’”

Ira’s skill extended beyond the fly reel as well. On many occasions, he engaged in a variety of fishing methods to provide sport for his clients. If the trout would not rise to a fly, he would turn to either worms or other bait. One of his secrets was baiting the hook with a “scientifically cut” piece of shiner, put on in a secret method that was never revealed but proved successful time and again. And the sportsmen who chose Ira Shires could always rest assured that their catch would kept fresh. Ira would take great care to clean and wash each fish carefully, and would make sure they were covered with leaves or else buried in a cool place if they were to be kept overnight.

As his notoriety spread, Ira’s clientele grew. He guided such notable men as naturalist George Lincoln Goodale, Rev. John Todd, who earlier had established the first church on Long Lake, and the inventor of the six-shooter, Samuel Colt.

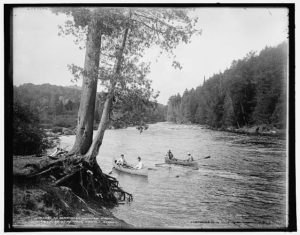

One of Ira’s favorite places was Fall Stream, which flows into Piseco Lake from the northeast. He seemed to know every spring hole and hiding place of trout along its meandering course. In those years before game laws, it was common for anglers to catch fifty or more trout each day. Near the head of Fall Stream is Vly Lake, which was a preferred destination of Ira’s for overnight trips. On the shore of the lake, he had a simple lean-to, where sportsmen would sleep on boughs of balsam with their feet warmed by a roaring fire. The meals on these trips mainly consisted of the trout that they caught, fried in bacon grease and served on a piece of rough bark.

In 1890, Ira Shires passed away at the age of seventy-two. During his lifetime he helped raise a family and, after years of failed farming, built a successful career in the profession he loved: Adirondack guide.

Sally Shires died in Piseco, two years after her husband. Thereafter, Clarence was sent to the Craig Colony for Epileptics in Sonyea, Livingston County, New York, where he passed away in 1902.

[Research material for this article came from the online newspaper archives, nyshistoricnewspapers.org and fultonsearch.org, as well as family trees and census records from ancestry.com. The map on the banner is taken from Wallace’s 1876 Map of the Adirondack Wilderness. The illustration of Ira Shires is from Amsterdam Democrat, July 7, 1886.]

Dave Waite is a Saratoga County writer, photographer, and lover of history. You can also find his work in The Gristmill.